Back in 2006, when I had not yet accepted the necessity of the concept of agency ("free will"), and was thus still an atheist and materialist, I wrote a short article (

qv) on how free will is "a problem for everyone" -- meaning that it is logical antinomy that is in no way solved by believing in God or spirits, and is thus not

just a problem for atheists.

In that article, I argued as follows:

1. If, as Studies Have Shown, I am the product of my genes and environment, less proximately of Darwinian evolution, and ultimately of the Big Bang, then I am not responsible for who I am or what I do, since I and my will are the product of things that existed before I did and are beyond my control.

2. If, as Classical Theology has it, I was created ex nihilo by God, then I am not responsible for who I am or what I do, since I and my will are the product of a Being that existed before I did and is beyond my control.

3. If, as many Mormons believe, my intelligence “was not created or made, neither indeed can be” (D&C 93:29), but has just always existed, just

because, then I am not responsible for who I am or what I do, since I and my will are as they are for no reason at all and are therefore no one's responsibility.

4. That exhausts the possibilities. Therefore, I cannot be ultimately responsible for what I do, cannot have "free will" in any straightforward sense, and must be content with some allegedly-close-enough substitute of the sort promulgated by the likes of Daniel Dennett.

I expressed my main point thus:

The bottom line is that you didn’t create yourself. Given that a cause must precede its effect, it’s logically impossible for you to have created yourself. No matter what you believe about human nature or human origins, it is inescapably true that you are not ultimately responsible for what you are; either something or someone else made you that way, or you are that way for no reason. No matter how you slice it, it’s not your fault.

In other words:

- I am an agent with free will.

- I can have free will only if I created myself.

- But it doesn't make any sense to say I created myself.

- Therefore, premise 1 is false, and I do not have free will after all.

⁂

A lot has changed in my thinking since I wrote that. Most importantly, I finally came, in 2013, to acknowledge the absolute

necessity of agency. I still couldn't see any flaws in my 2006 argument, though, so I just sort of set it to one side, turning a blind eye to some truths I had once faced, and reverted to my Mormon assumption that I and other free agents had always existed, for no particular reason.

Recently I have become increasingly dissatisfied with that assumption. For one thing, it seems inconsistent with the idea that we have endless potential and "it doth not yet appear what we shall be" (1 John 3:2). If I have already existed for an infinite period of time, it seems that I would long since have realized whatever potential I may have. For another, there is the point I made back in 2006: that if I exist just because I always

have, for no reason, then I and my actions are a brute fact of the universe and are no one's responsibility.

So now, while starting with the same premises as in 2006, different metaphysical priorities cause me to arrive at a different conclusion.

- I am an agent with free will.

- I can have free will only if I created myself.

- But it doesn't make any sense to say I created myself.

- But I do have free will, so I did create myself, and I'd better make it make sense.

I have broached this idea of self-creating, of "thinking ourselves into being," before, in my

notes on John 1:

When Descartes wrote “I think, therefore I am,” he meant “therefore” in the epistemic sense: the premise “I think” entails the conclusion “I am.” In the Primary Thinking model, though, it is true in the causative sense: I think, and as a result I exist. We each think ourselves into being and collectively think the cosmos into being. Thinking which is both free and true (i.e., Primary Thinking) is by its nature an uncaused cause.

Granted, immediately after writing that, I went on to quote D&C 93 on how "man was also in the beginning with God," not perceiving the contradiction. Now I would say that we, each of us, "thought ourselves into being" at a particular point in time, prior to which we did not exist.

⁂

One day, I decided to exist. "Let there be me," I said, and there I was.

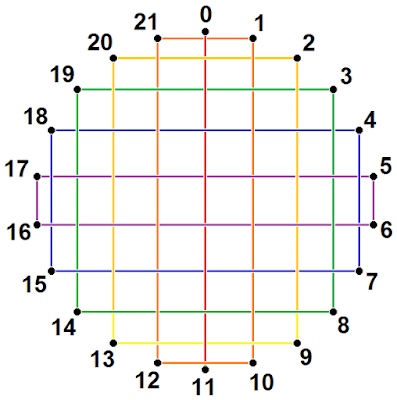

As should be clear from the picture with which I have chosen to illustrate this post, I am very much aware of the paradoxical nature of such an origin story -- but all possible alternatives are paradoxical, too, and (in my judgment) less tolerably so. The paradox of the self-creating agent is just another instance of the

type of paradox we already have to deal with anyway. It bears a certain similarity, for instance, to the familiar idea of the Big Bang; nor is it entirely dissimilar to any "ordinary" act of free will, which also partakes of the nature of an uncaused cause.

In classical theology, God is an uncaused cause whose existence is explained by the fact that it is supposedly

logically necessary -- that "There is no God" is logically false in the same way that "Some circles are squares" is false. This whole line of thinking is a category error; as Plato demonstrated through the mouths of some of his smart-ass Sophists centuries before Anselm of Canterbury, it is easy to "prove" that the non-existence of

anything is logically false. (Example: The Loch Ness monster is, by definition, a monster that lives in Loch Ness. But in order for anything to live in Loch Ness it must first exist; being in any particular place entails

being simpliciter. Therefore, "The Loch Ness monster doesn't exist" is self-contradictory; and the monster necessarily exists.) All predicates presuppose existence; what does not exist is nothing at all and has no characteristics. Thus, any statement of the form "P doesn't exist" is reducible to the contradiction "P is not P." What does not exist cannot be all-powerful or have four legs or live in Loch Ness, so how can it be God, a horse, the Loch Ness monster, or any other particular thing? (Thus later philosophers' insistence that existence is not a predicate. "P doesn't exist," while tolerated in many natural languages, is logically ill-formed, the correct expression being "There is no P.")

So this idea that God has necessary existence, in contrast to the contingent existence of everything else, is -- despite its acceptance by a number of distinguished thinkers -- basically a bad one, founded on what is almost literally a textbook example of sophistry.

If God doesn't exist necessarily, perhaps he just happens to exist for no particular reason -- "randomly," as it were. Although I didn't really think it through at the time -- at least not to the point where I would have countenanced the use of the word

random -- this is implicitly what I believed as a Mormon: that God and the other intelligences (including those that have since become humans) had always existed, just

because, and that there was no particular reason for it all. This is obviously unsatisfying.

Well, then, what is neither necessary nor random? In 2006 I would have said -- in fact,

did say -- "Nothing. Those two options exhaust the logical possibilities." Since then, though, I have found it necessary to admit a tertium quid into my ontology: agency, or free will. This, then becomes the preferred way of explaining the existence of free agents, including God: We each came into being because we chose to do so.

⁂

If each agent, including even God, has existed for a finite period of time, it opens the door to speculation -- and it is only speculation! -- regarding the relative

ages of different agents.

At first I assumed that God must be the very first agent to have come into existence, because anything else would be sort of "beneath his dignity." But of course that kind of thinking -- the granting to God of every conceivable superlative as a matter of course, lest we be guilty of lèse-majesté -- is the road that leads to classical theology with its incomprehensible omni-everything Nobodaddy whose center is everywhere and whose point is nowhere, the sort of God with respect to whom I am still what is called a "hard" atheist.

God

could be the oldest agent, of course, but there is no need to assume he is, and in fact I tend to think that he isn't. As man among the animals, as Christ among men, so is God among the agents. Man is very far from being the first animal to have appeared, and it remains to be seen how far he is from being the last. Christ is described (by Mormons) as having come at the "meridian of time" -- the exact midpoint of world history -- and at any rate he was very far from being the first man. Various traditions that have come down to us tell of how before the Gods there were Titans, daevas, jötnar, monsters. Even in the Bible there remain hints of God's having, like Marduk, done combat with primordial dragons that were, implicitly,

already there. If Our Father was far from the first to arrive on the scene, his advent would mark something corresponding to the BC/AD divide in world history -- dividing the morning of the cosmos from its afternoon. Is it by coincidence that the Enemy of mankind, called "the great dragon . . . that old serpent" in the Apocalypse, has been given also the titles "morning star" (for that is the meaning of

Lucifer) and "son of the morning"? Or what about that evocative old line in Job (a book perhaps older even than Homer): "when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy"? Could this be an allusion to the two great classes of agents -- before Our Father, the morning stars; after him, the sons of God?

Continuing with this speculation that at least some of the devils may be older and more primitive beings than God, we might venture the analogy Satan:Jehovah::Saturn:Jove. (Of course, the similarity of names is a coincidence without etymological foundation, but regular readers will know that I am not above taking note of coincidences.) I'm sure I can't be the first to have noticed how Revelation 12 alludes to the story of the birth of Zeus and the defeat of Kronos. The woman, like Rhea, gives birth to a child "who was to rule all"; the dragon, like Kronos, stands ready to devour the child as soon as it is born; the woman flees into the wilderness, like Rhea to her cave in Crete; a "war in heaven" ensues, and the losers are "cast out into the earth," as the defeated Kronos was cast down, either to Tartarus or to Latium. Of course I would not go so far as to say that Satan is God's "father," only that he may -- may! -- be one of the "Great Old Ones" from the morning of the cosmos.

In the King Follett Sermon (

qv), Joseph Smith asserts that God and all other agents have always existed: "God never had the power to create the spirit of man at all. God himself could not create himself. Intelligence is eternal and exists upon a self-existent principle. . . . and there is no creation about it." This clearly goes against my own proposal that God

did create himself -- but just after saying that, Smith goes on to speak of how "God himself,

finding he was in the midst of spirits and glory, because he was more intelligent, saw proper to institute laws whereby the rest could have a privilege to advance like himself" (italics added). Doesn't it sound as if God just appeared one day and "found himself in the midst of" an already-existing world? It was a world "of spirits and glory," too. The children of the morning were not all dragons and Hecatoncheires; among them were beings high and holy -- but not

divine, for divinity had not yet been invented.

Lucifer may or may not be a "son of the morning" in my conjectural sense of that term, but there can be little doubt that we ourselves are children of the afternoon. It was into God's world that we came into being, and we have from the beginning been under his loving guidance and protection, making our situation fundamentally different from that of the children of the morning. It is for this reason, and also because we have the potential to become like him, that we are called God's "children." Christ is presumably one of the oldest of the children of the afternoon; at least, the Fourth Gospel represents him as being older than both John and Abraham, despite the fact that his biological birth postdated theirs, and it has been conventional since Paul to call him the "firstborn."

⁂

This post is just me thinking out loud, and I'm not yet very sure about most of the ideas it contains. I will need some time to think it all over and sift out any genuine intuition from what is mere enthusiasm over something new and clever. In the meantime, I welcome comments.