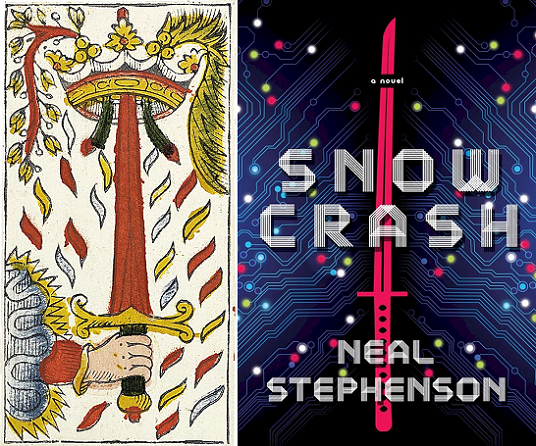

My last post dealt with syncs related to the Ace of Swords and the cover of the Neal Stephenson novel Snow Crash.

Initiation into the rites of Mithras, like initiation into many other ancient schools of philosophy, apparently consisted of three important degrees. Preparation for these degrees consisted of self-purification, the building up of intellectual powers, and the control of the animal nature. In the first degree the candidate was given a crown upon the point of a sword and instructed in the mysteries of Mithras' hidden power. Probably he was taught that the golden crown represented his own spiritual nature, which must be objectified and unfolded before he could truly glorify Mithras; for Mithras was his own soul, standing as mediator between Ormuzd, his spirit, and Ahriman, his animal nature.

Is this relevant to the image on the Ace of Swords? The bolded passage could mean that a crown is hung on the point of a sword and thus presented to the candidate, but Hall's Masonic background suggests another reading:

Senior Deacon steps back, while the Junior Deacon, with candidate, enters the Lodge, followed by the two Stewards. As they advance they are stopped by the Senior Deacon, who presents one point of the compasses to the candidate's naked left breast, and says:

S. D. -- Mr. Gabe, on entering this Lodge for the first time, I receive you on the point of a sharp instrument pressing your naked left breast, which is to teach you, as it is a torture to your flesh, so should the recollection of it ever be to your mind and conscience, should you attempt to reveal the secrets of Masonry unlawfully.

In the above passage, from Duncan's Masonic Ritual and Monitor, receiving the candidate "on the point of a sharp instrument" means receiving him while pressing the point of such an instrument against his body. In the same way, "upon the point of a sword" may have a meaning corresponding to that of "at gunpoint," meaning that the candidate is threatened with a sword as he is given a crown, as if the crown is being forced upon him.

Trying to track down Hall's possible sources in ancient literature, I found only a couple of passages in Tertullian. The first is from Prescription Against Heretics, Chapter LX:

He [the devil], too, baptizes some -- that is, his own believers and faithful followers; he promises the putting away of sins by a laver (of his own); and if my memory still serves me, Mithra there, (in the kingdom of Satan,) sets his marks on the foreheads of his soldiers; celebrates also the oblation of bread, and introduces an image of a resurrection, and before a sword wreathes a crown [sub gladio redimit coronam].

The translator calls the clause I have bolded "obscure," which it certainly is. A strictly literal reading would be "under a sword redeems a crown." Whatever that may mean, sub gladio ("under a sword") can't very well mean that the crown was on the sword.

The other Tertullian passage, from De Corona, Chapter XV, goes into somewhat more detail and seems likely to be Hall's source:

Blush, ye fellow-soldiers of his [Christ's], henceforth not to be condemned even by him, but by some soldier of Mithras, who, at his initiation in the gloomy cavern, in the camp, it may well be said, of darkness, when at the sword’s point a crown is presented to him [coronam interposito gladio sibi oblatam], as though in mimicry of martyrdom, and thereupon put upon his head, is admonished to resist and cast it off, and, if you like, transfer it to his shoulder, saying that Mithras is his crown. And thenceforth he is never crowned; and he has that for a mark to show who he is, if anywhere he be subjected to trial in respect of his religion; and he is at once believed to be a soldier of Mithras if he throws the crown away -- if he say that in his god he has his crown. Let us take note of the devices of the devil, who is wont to ape some of God’s things with no other design than, by the faithfulness of his servants, to put us to shame, and to condemn us.

This is literally "he is presented a crown with a sword interposed," which again seems unlikely to mean that the sword itself was "crowned," as in the Ace. I think that what Tertullian means is that the candidate is "forced" at swordpoint to accept the crown but is nevertheless supposed to reject it, expressing the fact that he would rather die than accept any other crown than Mithras himself. (Is there a pun here on Mithras and mitra, "mitre"?) It seems strange to us today, when almost nobody ever wears a crown, that not wearing one could be "a mark to show who" is a true follower of Mithras, but things were different in Tertullian's time. De Corona opens with this anecdote:

Very lately it happened thus: while the bounty of our most excellent emperors was dispensed in the camp, the soldiers, laurel-crowned, were approaching. One of them, more a soldier of God, more stedfast than the rest of his brethren, who had imagined that they could serve two masters, his head alone uncovered, the useless crown in his hand -- already even by that peculiarity known to every one as a Christian -- was nobly conspicuous. Accordingly, all began to mark him out, jeering him at a distance, gnashing on him near at hand. The murmur is wafted to the tribune, when the person had just left the ranks.

The tribune at once puts the question to him, "Why are you so different in your attire?"

He declared that he had no liberty to wear the crown with the rest.

Being urgently asked for his reasons, he answered, "I am a Christian."

O soldier! boasting thyself in God. Then the case was considered and voted on; the matter was remitted to a higher tribunal; the offender was conducted to the prefects. . . . and now, purple-clad with the hope of his own blood . . . and crowned more worthily with the white crown of martyrdom, he awaits in prison the largess of Christ.

Apparently, it was common practice for all the soldiers in a victorious army to be given laurel crowns, thus making Christians (and Mithraists) conspicuous in their refusal to wear them. In this story, the Christian expects to be put to death for this refusal, so he has, figuratively speaking, been presented with a crown "at the sword's point." Since Tertullians point is that the Mithraists sometimes put Christians to shame, we may presume that the Mithraic story has the same meaning: The sword symbolizes a threat should he refuse to wear the crown, and yet he is to defy the threat and refuse.

Tertullian's reference to "the white crown of martyrdom" is curious, since the term "white martyr," as contrasted with "red martyr," typically refers to someone who is persecuted for his faith but not killed. In the 1906 vision of Maximilian Kolbe, the white crown "meant that I should persevere in purity and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both." White apparently did not yet have this connotation for Tertullian, though, since he describes his white-crowned martyr as "purple-clad with the hope of his own blood."

Whatever Tertullian's reason for calling the crown of martyrdom "white," it syncs with the Snow Crash cover, where the word snow appears in place of the crown.

1 comment:

The white crown also syncs with Stephanie South ("crown of the south"), because of the two crowns of ancient Egypt. The Red Crown of Lower Egypt was called Deshret, "red one"; and the White Crown of Upper (i.e., southern) Egypt was called Hedjet, "white one."

Post a Comment